I never felt the influence of Muriel Spark, despite the fact that she was a substantial female figure in British literature. It’s a pity, because there was much to learn from her macabre, entirely unsentimental art and its account of the strange violence of living. It was only quite recently, when I came across a new volume of her collected letters (meticulously edited by Dan Gunn), that I first felt confronted by her persona. The letters invited an investigation into both the life and the work.

“The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie” (1961) was Spark’s best-known novel, and was also the basis for a very successful film starring Maggie Smith. It was this film, perhaps, that cheapened Spark’s influence in my eyes when I was a young writer: the film was popular and funny, qualities it is difficult to associate with this writer at her savagely satirical best. The letters show that she was greatly inflated by the success of “Miss Jean Brodie,” and the material and cultural power it signified. She came from a disordered and working-class Scottish background and was the single parent of a child whose mentally ill father continually harassed her. Her life was a perennial effort to secure money and recognition in a literary scene dominated by educated male snobs. As is often the case, the tireless instinct of creativity generally thwarted this effort. But with “Miss Jean Brodie” Spark managed to please more conventionally.

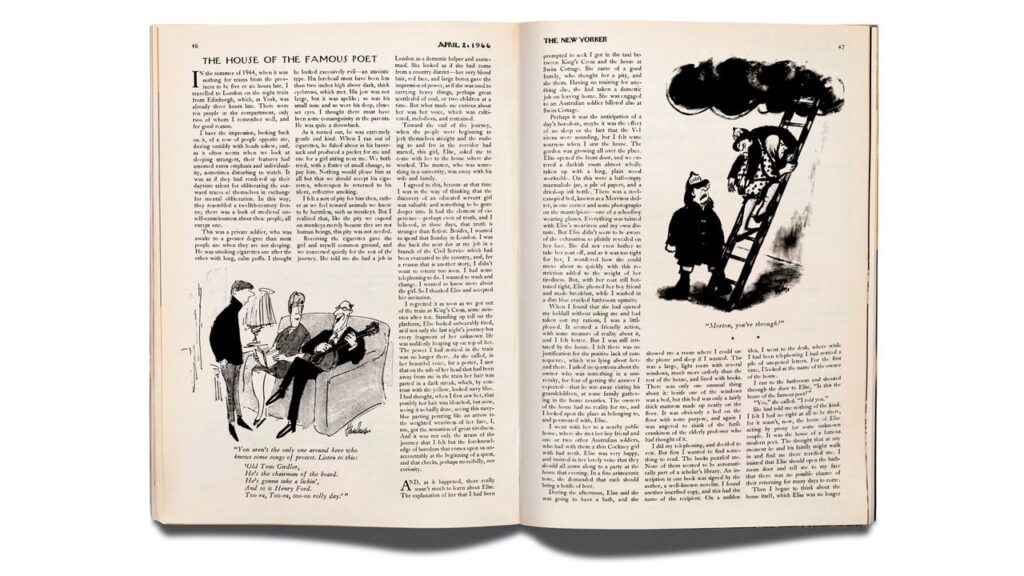

The story “The House of the Famous Poet,” which was published in The New Yorker five years after “Miss Jean Brodie,” has many of the hallmarks of Spark’s best writing. Her natural and melodious style, so swift and unpretentious, bears death and danger on its wings. The story begins in an autobiographical tone, with the narrator on a train from Edinburgh to London, in 1944. The feeling of an elemental unsafety that is somehow joyously—or at least spiritedly—borne is established straight away in the description of a soldier in the train carriage who looks “excessively evil” but turns out to be “extremely gentle and kind.” Spark did write autobiography, but the autobiographical tone is relatively rare in her fiction. Usually, she liked to hold her fictional world and the people in it at a greater distance, so that she could inflict violence on them. In this story, the violence is already all around: it is toward the end of the Second World War, and the world is in smoke and ruins. The people in the train carriage—along with the narrator—are living in the threadbare moment.

I took several things from the story: the atomizing nature of catastrophe, which yet grants a peculiar clarity of perception; the electric influence of fame; the haphazard quality of experience, which militates against narrative; and the unstructured possibilities of female association. The story culminates in the idea of an “abstract funeral”: I was intrigued and moved by this but couldn’t find a way of answering it in my own story, “Project.” I did, however, take two lines from the opening of “The House of the Famous Poet” and put them largely unaltered into my story—a genuflection to the master.

Muriel Spark never forgot the presence and the moral problem of evil. It can be uncomfortable to read her, because, while she certainly offers no refuge in narrative, she offers little in art either. There is no zone of privilege in her work—absolutely anything can happen at any time. She assumes very little, takes little for granted, and so the visual or perceptual plane of her writing is unusually heightened. In another writer, this might bespeak a form of marginality, the person who observes because she is fundamentally powerless. In Spark, the effect is hallucinatory, resulting in a type of hyperreality that, to me, constitutes an interesting representation of the intellectual experience of femininity. The female alone, unconsoled by the myth of her cultural safety, equally unconcerned with the question of her actual vulnerability, is a constant figure in Spark’s fiction. She is a kind of lightning rod, attracting the world’s terror and fire and conducting its truth, rather than resisting or shaping it.

I’m not sure who the famous poet was, though I suppose I could find out. ♦

The House of the Famous Poet

The House of the Famous Poet

It had the element of experience—perhaps even of truth, and I believed, in those days, that truth is stranger than fiction.

Disclaimer: This post is sourced from an external website via RSS feed. We do not claim ownership of the content and are not responsible for its accuracy or views. All rights belong to the original author or publisher. We are simply sharing it for informational purposes.