Environment

/

Books & the Arts

/

August 25, 2025

Is all the hope placed in renewables an illusion?

Ad Policy

A worker in a coal yard in the Sonbhadra district of Uttar Pradesh, India, 2021.

(Ritesh Shukla / Getty Images)

In universities, labs, corporate research departments, think tanks, and intergovernmental organizations, thousands of smart, qualified experts are working away (or at least those who still have funding are working away), devoting billions of dollars and millions of hours to a problem they collectively refer to as “the energy transition.” The idea is simple: Human society once ran exclusively on photosynthetic sources of energy such as wood and animal power; then the Industrial Revolution brought about a transition to fossil fuel energy in the form of coal, which was later replaced by oil. The fossil fuel economy has become untenable on a planetary scale, so we must now bring about another transition, to renewable energy, through a huge project of innovation (facilitated by a heretofore unseen level of collaboration between the public and private sectors). The transitions of the past, the experts say, should provide helpful examples for how we can pull off such a feat. This monumental effort, we are told, is our best hope for surviving climate change. But according to the French historian of science Jean-Baptiste Fressoz, the battle is already lost. We are in a lot of trouble.

Books in review

More and More and More: An All-Consuming History of Energy

In More and More and More: An All-Consuming History of Energy, Fressoz sets out to show that there is no such thing as an “energy transition,” and there never has been. To put it bluntly: “After two centuries of ‘energy transitions,’ humanity has never burned so much oil and gas, so much coal and so much wood. Today around 2 billion cubic metres of wood are felled each year to be burned, three times more than a century ago.” Instead, Fressoz’s coruscating history looks to explain “why all primary energies have grown together and why they have accumulated without replacing each other.” Far from being an established empirical fact about the past, the “energy transition” began as “a heterodox and mercantile futurology—a mere industrial slogan—which, from the 1970s onwards, became the future of experts, governments and companies, including those that had no interest whatsoever in seeing it happen.”

The book splits cleanly into two halves. The first relentlessly piles up factual evidence to show that coal did not replace wood and oil did not replace coal. Rather, the production of each has entailed an intensification in the use of the others, such that the global history of energy can be seen as one of constant accumulation and the continued persistence of older techniques, not one of epochal technological transitions. The second half of the book traces the emergence and rise to intellectual dominance of the concept of “energy transition” itself. In this way, More and More and More is both a material history and an intellectual one, or as Fressoz puts it, “the politics of history in the face of climate change.”

Fressoz is a widely published historian of science who, along with Christophe Bonneuil, wrote The Shock of the Anthropocene (2015), a field-defining book that both dissects the concept of the “Anthropocene” and provides the most concise and terrifying digest of the postwar “Great Acceleration” in climatic destruction yet written. If one person is going to shout in public that the emperor is naked, Fressoz is among the most persuasive candidates.

Much of More and More and More makes for devastating reading. By considering the entirety of a production chain instead of just its output or its main source of power, Fressoz reveals that all of our economic systems are mutually dependent, and have been for centuries. The growth of the coal industry in the 19th century, for instance, depended on an immense amount of timber to prop up the mines and to transport the coal in ships and carts. With the introduction of chain saws in the 20th century, wood production became oil-intensive, such that “2 to 3 litres of diesel are consumed per cubic metre of wood extracted, meaning that wood has become, in part, a fossil fuel.” Forestry productivity has increased to keep up with demand, but it has done so through the use of chemical fertilizers that are oil-intensive to produce. And oil never really replaced coal: Cars drive on roads made of concrete, which is produced with coal, to the degree that about half a ton of coal is burned for every meter of concrete road. The first oil rigs were made of wood, as were the barrels that oil was transported in. Strip-mining for coal runs on oil-intensive machines, so even in surface mines it takes “between 1 and 2.5 litres of diesel to extract one tonne of coal.” And so on.

Even if it were possible to decarbonize electricity production (and recent work by Brett Christophers persuasively argues that it is not, at least not within market institutions), that still would not decarbonize the production of cement, steel, plastic, and fertilizers, which together account for a quarter of global emissions, and much of which would be used intensively in the production of whatever systems of solar and wind power would be needed for shifting the global electricity grid from fossil fuels to renewables.

Current Issue

If Fressoz is right—and he certainly is very convincing—how is it possible that so many intelligent people are spending so much money working on so many projects around the world to chase an impossible illusion?

When and where did the idea of an energy transition emerge? Fressoz argues that it originated in the Great Depression. Many scientists and engineers, inspired by the late work of Thorstein Veblen and a belief in the rational management of society, feared that the global economic downturn was the outcome of an energy transition gone wrong: The previous decades of industrial growth (in America especially) had generated a huge amount of output by marshaling an even larger amount of energy. That replacement of human power by electrical power was thought to be the cause of mass unemployment, even in the face of overproduction and overcapacity. Electricity had been the source of rapid growth, but it suddenly seemed to be the source of a structural crisis as well. This was understood to be a new puzzle requiring scientific management to solve. The members of this “technocracy movement” of the 1930s produced new kinds of statistical tools, especially the S-curve, which shows first exponential growth and then diminishing returns, thereby illustrating how apparently rapid growth is unsustainable. A group of scientists and engineers called the Technical Alliance used these curves in an unfinished report on energy usage in the United States, aiming to show that the unregulated capitalist system was wasteful.

The technocracy movement did not survive the interwar period: Some of its members embraced Herbert Hoover, who called himself America’s “chief engineer,” while others enthusiastically supported the New Deal’s expansion of technical management and regulation. The movement’s eccentric leader, Howard Scott, liked isolationism and quasi-military parades, which grew unattractive in the early 1940s. Yet, while the movement’s interpretation of the Depression did not last, its statistical tools did. In the postwar era, boosters of atomic energy used S-curves to show the inevitable decline of oil production, thereby creating the idea of “peak oil.” The same curves were used to illustrate future predictions for all sorts of things, from economic and population growth to person-hours per unit of production and industrial employment. These predictions were then marshaled for political advocacy. Across an increasing range of social and economic indicators, the “atomic Malthusians” (to use Fressoz’s delightful phrase) envisioned a future of finitude, one rife with population catastrophes, food and energy shortages, and economic decline that could only be prevented by a transition to nuclear energy. The term “energy transition” itself was coined by the former Manhattan Project nuclear chemist Harrison Brown in 1967, at a conference of neo-Malthusians discussing food and family planning.

The transition concept was embraced in nuclear policy advocacy, but it remained limited in its application until it intersected with another newly transformed idea. In the 1970s, the concept of an “energy crisis” (a sharper version of “energy transition”) was transformed from an ecological critique of too much energy to a policy critique of too little energy in the moment of oil price shocks, gasoline rationing, and the image of Jimmy Carter’s solar panels on the White House. Thus the idea of an “energy transition” as a solution to the “energy crisis” entered the realm of public discussion, all oriented around the need to find a more reliable and abundant source of energy that couldn’t be choked off by OPEC. And finally, after the 1970s, a number of free-market economists (among them Nobel laureate William Nordhaus) and fossil fuel companies like Exxon began using statistical projections of the future to argue that innovation and technology would inevitably find solutions to the possibility of climate disaster, thus obviating the need for any urgent action, let alone regulation. Emissions and fossil fuel use, they claimed, would also follow a reassuring S-curve pattern, and new technologies would benefit from the rapid upward slope of the first part of the curve while old ones tapered off. “The alignment of these inherently polluting industries under the banner of energy transition has at least one merit,” Fressoz writes: “It clarifies the ideological function of this notion. Energy transition has become the politically correct future for the industrial world.”

In this way, Fressoz means to show two things: first, that the idea of “energy transition” was long a fringe belief associated with Depression-era industrial theorists, radical environmentalists, and atomic Malthusians, all people whom respectable mainstream scientific opinion would probably disavow today. And second, that the conceptual and empirical toolbox of S-curves, future discounting, and transition dynamics invented in one time and place has gone on to serve different purposes in others, especially regarding our ability to imagine the future. “Transition,” Fressoz writes, “projects a past that does not exist onto an elusive future.”

Ad Policy

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Any discussion of capitalism, climate change, and the future must eventually invoke Fredric Jameson’s observation that it is easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism. Fressoz does so here, to chilling effect, in his discussion of Group III of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which is the working group on mitigation. They have adopted wholesale the innovation paradigm from the fossil fuel industry to imagine a preposterous future—of infinite growth made possible by marine cloud seeding and space mirrors, all purely hypothetical—thereby foreclosing the possibility of changes to the institutions of capitalism. Fressoz heaps scorn on their hectic ideas, such as burning fast-growing trees in an amount greater than the world’s total wood production, then burying the carbon in the ground indefinitely. “Some experts within Group III of the IPCC,” he writes, “will have entertained visions of liquefied CO2 lakes resting on the ocean floor before considering the reduction of the size of any national economy.”

From this, Fressoz reaches a damning conclusion: “Transition is the ideology of capital in the twenty-first century,” and our faith in innovation and technology as a solution “is preventing us from having an adult conversation about climate change.”

This is strong stuff, and the stakes are perilously high. Some readers are likely to object to the way that Fressoz counts inputs and intermediary goods in production—but that is exactly his point. We have created conceptual tools—including measuring economies within national borders, not production chains—that do not allow us to see the actual materiality of any economic process from beginning to end. Others will object that Fressoz does not clearly set out what he thinks the missing “adult conversation” should look like, aside from several references to degrowth. At 320 pages, the book is brief enough that I do wish he had taken that point on explicitly, because his commitment to unsparing realism might have provided new insights into the common critique of degrowth: namely, that the world is profoundly unequal, so an end to growth will either create permanent inequality or depend on a politically implausible program of global redistribution. If that is the adult conversation, it needs to start.

It must also be said that this is a profoundly bleak book. The central hope for human survival held by most experts, technocrats, politicians, and the alarmed general public is not only a fiction, Fressoz insists, but an active impediment that has set back action by decades, to such a degree that it is now probably too late. All that work on mitigation has been dithering around the margins, mainly acting as cover and public relations for egregious polluters and emitters, at best producing some moderate process improvements that have immediately been offset by increases in total production or the geographical redistribution of the most obviously harmful activity to poorer countries.

Fressoz is adamant that there is no realistic possibility of carbon-free material abundance, and that the world is not thinkable without plastic, fertilizer, and cement, the building blocks of modern life, which cannot be decarbonized even under a transition to electricity from solar and wind. Perhaps, then, the adult conversation is about what a world of permanently declining material standards will look like. If so, it is difficult to feel confident that all those mitigating and innovating scientists, lawyers, policy wonks, and academics will pivot to working collectively on a program of global redistribution rather than continuing to do what they have done for decades, which is serve the interests of capital. Meanwhile, those opportunistic enough can make a quick buck on fantasies of energy transition, while any project of redistribution faces bigger and bigger obstacles, with less and less time and resources available.

In this moment of crisis, we need a unified, progressive opposition to Donald Trump.

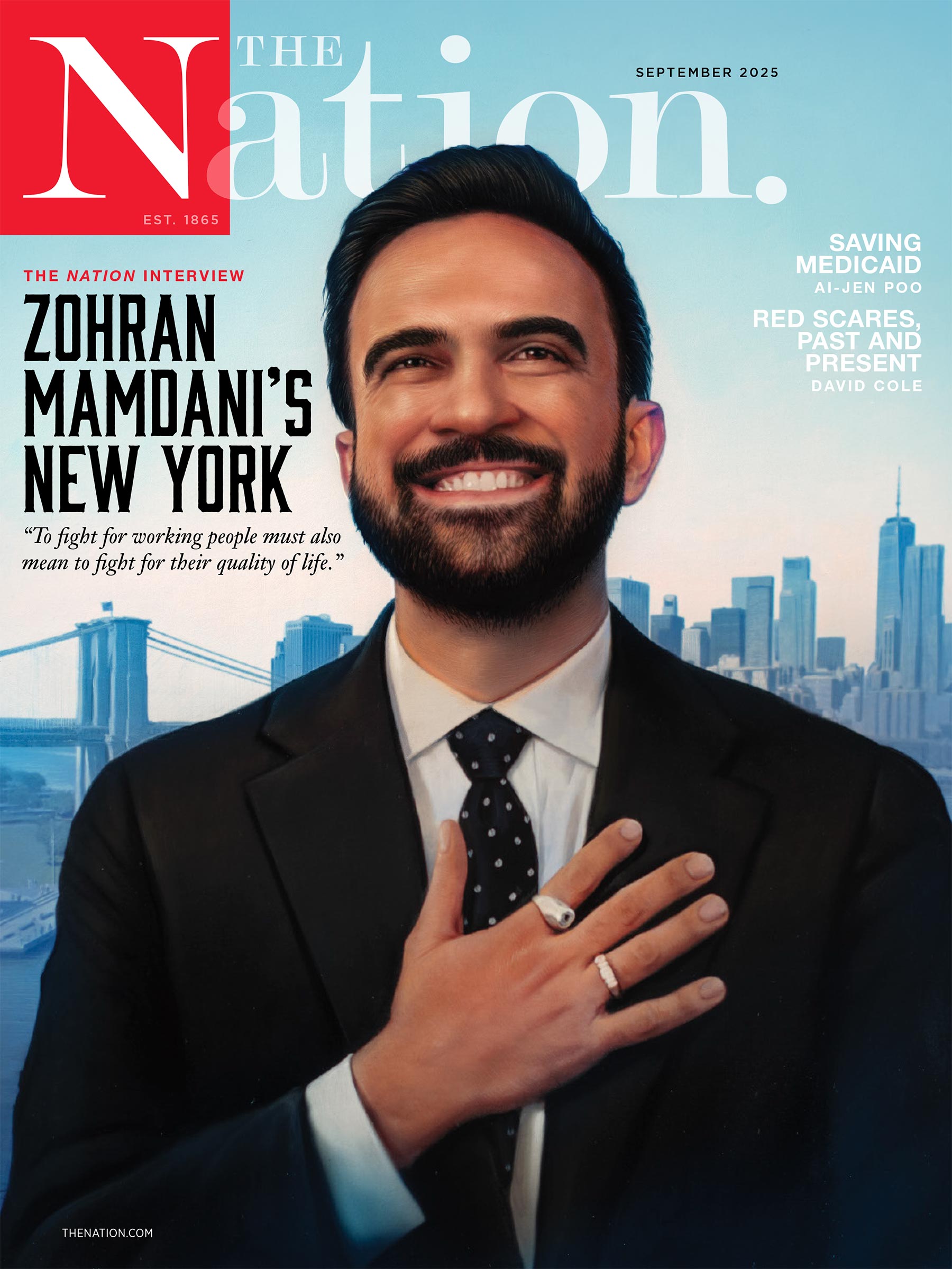

We’re starting to see one take shape in the streets and at ballot boxes across the country: from New York City mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani’s campaign focused on affordability, to communities protecting their neighbors from ICE, to the senators opposing arms shipments to Israel.

The Democratic Party has an urgent choice to make: Will it embrace a politics that is principled and popular, or will it continue to insist on losing elections with the out-of-touch elites and consultants that got us here?

At The Nation, we know which side we’re on. Every day, we make the case for a more democratic and equal world by championing progressive leaders, lifting up movements fighting for justice, and exposing the oligarchs and corporations profiting at the expense of us all. Our independent journalism informs and empowers progressives across the country and helps bring this politics to new readers ready to join the fight.

We need your help to continue this work. Will you donate to support The Nation’s independent journalism? Every contribution goes to our award-winning reporting, analysis, and commentary.

Thank you for helping us take on Trump and build the just society we know is possible.

Sincerely,

Bhaskar Sunkara

President, The Nation

Trevor Jackson

Trevor Jackson is an economic historian at the University of California at Berkeley. His first book, Impunity and Capitalism: The Afterlives of European Financial Crises, 1690–1830, was published in 2022.

More from The Nation

Ari Aster’s farcical western is billed as a send-up of the puerile politics of the Covid years. In reality, it’s a film that seems to have no politics at all.

Books & the Arts

/

Kelli Weston

Seth Harp exposes how all the death and crime surrounding one military base is not an aberration but representative of the fratricidal impulse of the armed forces at large.

Books & the Arts

/

Lyle Jeremy Rubin

How the fabled Hollywood director confronted survivor’s guilt, the legacies of the Holocaust, and the paradoxes of Zionism.

Ben Schwartz

In her most personal work, “The Möbius Book”, Lacey uses a devastating moment of heartbreak to ruminate on the messy intersections between life and writing.

Books & the Arts

/

Alana Pockros

Disclaimer: This post is sourced from an external website via RSS feed. We do not claim ownership of the content and are not responsible for its accuracy or views. All rights belong to the original author or publisher. We are simply sharing it for informational purposes.